Last summer, we were still in the midst of a pandemic, and I was overcome by grief over losing my dog, Sophie-Bea. I am still grieving, but I have been busy in graduate school, studying ecopoetics and marine biology at University of Maine–as a graduate student in the Interdisciplinary PhD program. While I was in the throes of grief last summer, I made my way to the midcoast Maine region, to my mother’s house near the river, and swam as often as I could. The river soaked up my tears, and I felt comforted by that. Swimming through eelgrass has always rejuvenated my spirits. Is it because I came of age in an eelgrass meadow, kicking against the current in the cold, cold waters of the Gulf of Maine? Eelgrass beds provide critical nursery habitat for young marine creatures, baby fish, juvenile lobsters, winter flounder, as well as horseshoe crabs, and other estuarine life in the Gulf of Maine. During the full moon in Pisces, I collected some seawater from the river, as well as a jar-full of eelgrass, so that I could study it, even after I returned to my home in the town known for the “land-locked salmon” near Sebago Lake. I’ve had a ritual of collecting “moon water” (on the full moon in Pisces every year) for over 25 years, but I’m also so fond of eelgrass. I did not pick (or harvest) the eelgrass. It was floating in the river, and snagged in some rockweed.

Stetson photo

A rooted, submerged aquatic flowering plant, Zostera marina, commonly known as eelgrass, is a pantemperate seagrass that grows globally along coasts and prefers sandy to muddy sediment in the lower intertidal zone of estuarine and marine environments. By “pantemperate,” I refer to the wide range of temperature (0-30°C) and salinity levels (10-30 ppt) that eelgrass tolerates, taking root in sandy bottoms as well as muddy areas, and it even grows in tide pools. (Tyrrell, 2005)[1] Eelgrass beds, or meadows, make ideal nurseries and Essential Fish Habitat (EFH) for invertebrates, young fish, and other marine life. (Lazzari, 2015) Eelgrass meadows provide EFH as nursery areas for young fish and shellfish species as well as providing refuge from predators, especially those which rely on visual-predation strategies (they see prey), as smaller fish and invertebrates can hide in dense meadows.[2] Marine scientists study Zostera marina for another reason: like other seagrass meadows, eelgrass beds sequester carbon, and that carbon sequestration potential is known as “blue carbon,” with implications for climate change, carbon budgets, and climate mitigation schemes in coastal communities. There are over fifty species of seagrasses worldwide; of those, Zostera marina is the most widespread seagrass species in the temperate northern hemisphere in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.[3] (Olsen, Rouze, et al. 2016) Between the ecosystem services that eelgrass meadows provide, including EFH and nutrient retention, and carbon sequestration and erosion control, seagrass meadows are still ranked as “among the most threatened on Earth.” (Waycott, et al. 2009; Olsen, et al. 2016)

In my exploration of eelgrass as a marine biology student, I have been learning more about its fascinating biology, its ecological relationships within estuarine and coastal ecosystems, and how eelgrass is also used in sustainable living design. As a mixed media artist, I have also been returning to a love for making “seaweed art,” something that I used to do (in the 1990s, early 2000s, and in 2018), and marine biology-themed illustrations of eelgrass and some of the marine life that depends on seagrass meadows for survival. Sea turtles depend on seagrasses, for example, and I made this watercolor of a Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) foraging in Turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum):

Zostera marina L. as ‘Essential Fish Habitat’ (EFH) for Young Fish

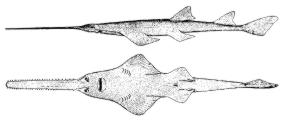

A marine resource scientist and ichthyologist with the Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR), Mark Lazzari conducted a study on “Eelgrass (Zostera marina) as ‘Essential Fish Habitat’ for Young-of-the-Year winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) in Maine estuaries.” (Lazzari, 2015) Lazzari defined “Essential Fish Habitat” as “the waters and substrate necessary to fish for spawning, breeding, feeding, and growth to maturity.” (Lazzari, 2015) Eelgrass meadows are considered “nursery areas” and provide a refuge to certain species from predators. (Lazzari, 2015) Comparing study data from 2003-2004, Lazzari argues that knowledge of eelgrass meadows is important because “shallow inshore habitats act as nurseries and feeding grounds, are environmentally variable, and subject to anthropogenic impact.” In the case of winter flounder, the “year-of-the-young” fish aged 0- x months, are “estuarine-dependent” in their early life stages. (Lazzari, 2015) “Beds of eelgrass, Zostera marina, represent a valuable habitat for shallow-water fishes including winter flounder and decapods.” (Lazzari, 2015) Moreover, the value of eelgrass as critical fish habitat as eelgrass is a “good predictor” of “winter flounder abundance” in Mid-Atlantic eelgrass meadows, and “small, dense patches of eelgrass may reach a carrying capacity, causing more extensive use of other habitats. (Lazzari, 2015) This leads to implications for future possible research on faunal density and “carrying capacity” in eelgrass meadows in Maine. Midcoast, Maine estuaries are often selected as study sites because of the coastal morphology and deep, narrow, strike-aligned estuaries. (Lazzari, 2015) Lazzari’s work has inspired my curiosity to research eelgrass in midcoast Maine estuaries, especially in the context of EFH for species like winter flounder. While I was reading Lazzari’s studies, and the state’s Wildlife Action Plan for 2015-2025, I felt inspired to make this quick sketch in my art journal.

Phylogeny of Eelgrass (Zostera marina)

Based on the entry in the AlgaeBase, Carl Linnaeus included classification of Zostera marina Linnaeus (often written as Zostera marina L.) in his 1753 publication, Species Plantarum (May 1753). The taxonomic classification is listed here, below (credit to AlgaeBase and Carl Linnaeus):

Empire/Domain: Eukaryota

Kingdom Plantae

Phylum Tracheophyta

Subphylum Euphyllophytina

Infraphylum Spermatophytae

Superclass Angiospermae

Class Monocots

Subclass Alismatidae

Order Alismatales

Family Zosteraceae

Genus Zostera

Species marina

Stetson photo

In recent years, phycologists have traced the phylogeny of Zostera marina in relation to other seagrasses and the “Tree of Life” and discovered that the genome shows indications that it adapted to living in a marine environment, and this is a special achievement for a flowering plant—an angiosperm. In their study, Dr. Jeanine Olsen, who specializes in marine benthic ecology, and colleagues, found that as the seagrasses evolved, through convergent and reversal evolution, Zostera marina and another grass, a freshwater species called freshwater duckweek (Spirodela polyrhiza) must have “diverged between 135 and 107 million years ago (Mya) and phylogenomic dating of the Z. marina suggests WGS (Whole genome shotgun approach) that it occurred 72-64 Mya.” (Olsen, Rouze, et al. 2016) Olsen and her team mapped the signatures of gene families onto a phylogenetic tree showing where Zostera marina enters the picture. To put this into context with related seagrasses, one of the oldest known plants is a clone of a Mediterranean seagrass, Posidonia oceanica commonly known as Neptune grass, which is about 200,000 years old, dating back to the Ice Age of the late Pleistocene.[1] (See Smithsonian)

Based on the genomic sequencing research that Dr. Olsen and her colleagues published in 2016, however, the first of its kind in sequencing the genomic phylogeny of any seagrass, their findings suggest that perhaps Zostera marina L. is one of the oldest seagrasses. (This remains an uncertainty, however, as there is an opportunity for genomic sequencing of other seagrasses for comparison.) Among their findings, Zostera marina “lost its ultraviolet resistance genes” adapting it to live comfortably in a marine environment, where it receives fluctuating and “shifted spectral composition,” unlike terrestrial flowering plants. (Olsen, Rouze, et al. 2016) Zostera marina also displays signatures of salt-tolerant genes, and “re-evolved new combinations of structural traits related to the cell wall,” (Olsen, Rouze, et al. 2016) creating a “cell wall matrix” that includes zosterin and “macroalgal-like sulfated polysaccharides.” (Olsen, et al. 2016) This is a key adaptation for a terrestrial plant. Zostera marina also “possesses an unusual complement of metallothioneins,” (Olsen, et al. 2016) chelators, or compounds that form complexes with metal ions, aid the plant in stress resistance. I find this so fascinating!! References are below.

While I am completing my graduate coursework, I will do my best to add fresh content to this blog. I am sorry I have been away from blogging–which I love to do–but it’s really been due to a combination of mourning my dog, and my focus on grad school.

[1] Details on Neptune grass found on the Smithsonian webpage for Seagrasses: https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/plants-algae/seagrass-and-seagrass-beds

[1] Tyrrell, Megan C. NOAA Coastal Services Center Fellow. “Gulf of Maine Marine Habitat Primer.” Ed. Peter H. Taylor. Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment. 2005 www.gulfofmaine.org

[2] Lazzari, Mark A. “Eelgrass, Zostera marina, as essential fish habitat for young-of-the-year winter flounder, Pseudopleuronectes americanus (Walbaum, 1792) in Maine estuaries.” Journal of Applied Ichthyology. Vol. 31. 2015. Pg. 459-465

[3] Olsen, Jeanine L., Pierre Rouze, et al. “The genome of the seagrass Zostera marina reveals angiosperm adaptation to the sea.” NATURE. Vol. 530. February 18, 2016. Pg. 331-347