On 8th Grade “Career Day,” my classmates and I were asked what we wanted to be when we grew up. I remember looking at a giant phonebook-sized directory of “careers” with code-keys for filling out a handout in class. I chose “marine biologist,” “oceanographer,” and asked my teacher, “where’s the code for “Ichthyologist?” Admittedly, I also wanted to write down on my sheet that I

Rachel Carson, marine biologist, author of The Edge of the Sea, Under the Sea Wind, and Silent Spring. Alfred Eisenstaedt photo, Time Life Picture

considered “mime” and “poet” to be future, possible careers, but only one of those was true. Poetry remains a constant passion for me, and so does ocean conservation. I grew up reading poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay and essays by Rachel Carson, including her book, A Sense of Wonder and later in high school, The Edge of the Sea, which remains one of my favorite books of all time. In 9th grade, I bought a text book on marine biology with babysitting money and studied it outside of school, over the summer, while I studied biology at Gould Academy. Years later, at College of the Atlantic (COA), I studied conservation biology, island ecology and environmental sciences as an undergraduate student. During a summer field course, my COA classmates and I explored over 30 Maine islands and visited Gran Manan, where we saw a 30-foot basking shark in the Bay of Fundy. Studying at COA, usually in a salt-sprayed hammock overlooking the ocean, definitely helped to shape my early passion for islands, oceans and wetlands into a career in conservation.

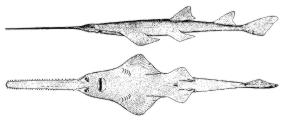

Sharks, rays and sawfish have always been fascinating to me. (Ocean conservation nerd alert: I even have a notepad from the American Elasmobranch Society on my desk.) I’ve spent some significant time on wetlands in my career, but I’ve also followed ocean conservation with great interest, never leaning too far away from my coastal roots. One area of ocean conservation that has kept my interest over the last two decades has been rare and endangered marine species, such as sawfish, which is the first sea fish to be listed on the U.S. Endangered Species list. In recent years, there’s been some hope for sawfish populations in South Florida (see this video). Yet, rules published by the National Marine Fisheries Service listed five species of sawfish as endangered this past month in its final ruling.

“The final rule contains the Service’s determination that the narrow sawfish (Anoxypristis cuspidate), dwarf sawfish (Pristis clavata), largetooth sawfish (collectively, Pristis pristis), green sawfish (Pristis zijsron) and the non-U.S. distinct population segment (DPS) of smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) are endangered species under the ESA.” (Miller, December 2014) (See info on the rule in the Federal Register here.)

What makes a thing like the sawfish rare?

Rarity is driven by scale—how many, how much, how big an area. Rarity means that something occurs infrequently, either in the form of endemism, being restricted to a certain place, or by the smallness of a population. In conservation biology the proportion or percentage of habitable sites or areas in which a particular species is present determines the rarity of a species.[1] In addition to the areas in which a particular species is present, the number of individuals found in that area also determines its rarity. There are different types of rarity which can be based on three factors: 1) geographical range – the species may occur in sufficient numbers but only live in a particular place, for example, an island; 2) the habitat specificity – if the species is a “specialist,” meaning it might be confined to a certain type of habitat, it could be found all over the world but only in that specific habitat, for example, tropical rainforests; 3) the population size – a small or declining population might cause rarity. [2] Generally a species can be locally very common but globally very uncommon, thereby making it rare and furthermore, valuable. A species can also be the opposite, globally common but spread out few and far between so that individuals have a hard time sustaining their populations through reproduction and dispersal.

But usually when a person thinks of rarity, they are probably thinking about a species that occurs in very low numbers and lives in only one place, as in many of the endemic creatures on the Galapagos Islands. It is this latter-most perception of rarity that plays a critical role in conservation work. People value rarity because it makes a living thing special—even if it had intrinsic value before it became rare, if it ever lived in greater numbers or more widespread populations.

Sawfish are a rare, unique—and critically endangered group of elasmobranches—sharks, skates and rays, that are most known for their toothed rostrum. Once common inhabitants of coastal, estuarine areas and rivers throughout the tropics, sawfish populations have been decimated by decades of fishing and survive—barely—in isolated habitats, according to the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida. Seven recognized species of sawfish, including the smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata), are listed as critically endangered by the World Conservation Union. In addition to the extensive gillnetting and trawling, sawfish are threatened by habitat degradation from coastal development. Sawfish prefer mangroves and other estuarine wetlands. Currently the sawfish population is believed to be restricted to remote areas of southwest Florida, particularly in the Everglades and the Keys. Sawfish are primarily a freshwater-loving creature but they occasionally go out to sea. Lobbyists proposed to add sawfish to Appendix 1 of CITES in 1994 (as part of the first Shark Resolution) to stop the trade in saws but the proposal was defeated in 1997 because it could not demonstrate that stopping trade would provide the necessary protection in wild populations. [See Petition to List North American Populations of Sawfish, 1999, here.] Subsequent proposals in 2007 and 2013 were successful, according to Shark Advocates International. According to the Mote Marine Laboratory conservation biologists, “even if effective conservation plans can be implemented it will take sawfish populations decades, or possibly even centuries, to recover to post-decline levels.” This is the fundamental crux of rarity in conservation biology: even if we do perfect conservation work, once a species is rare and critically endangered, it can take much longer for a species to recover than the time it took to reach the brink of extinction. In November 2014, all sawfish species were listed on Appendix I & II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS).

Sonja Fordham of Shark Advocates explains to me: The listing of smalltooth sawfish is therefore the most relevant; it has resulted in critical habitat designation, a comprehensive recovery plan, cutting edge research, and encouraging signs of population stabilization and growth.

See this NOAA Fisheries video on smalltooth sawfish conservation.

Several different organizations, in addition to federal and state agencies, are working to protect and conserve sawfish habitat and the endangered species. Here are some links to a few of these organizations and their fact sheets on sawfish:

Shark Advocates, Fact Sheet on Smalltooth Sawfish

Florida Museum of Natural History, Sawfish Conservation

Save our Seas, Conservation of Sawfish Project

Fact sheet for the 11th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP11) to the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) on Sawfish (5 species)

IUCN Global Sawfish Conservation Strategy

[1] Begon, Michael, John L. Harper, Colin Townsend. Ecology: Individuals, Populations, and Communities. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, London, et. al. 1990. Glossary pp. 859..

[2] Pullin, Andrew. Conservation Biology. Cambridge University Press, 2002. pp.199-201.